Max Dupain, Hungarian String Quartet, 1937

Max Dupain, Hungarian String Quartet, 1937 Olive Cotton, Hungarian String Quartet, 1937

Olive Cotton, Hungarian String Quartet, 1937

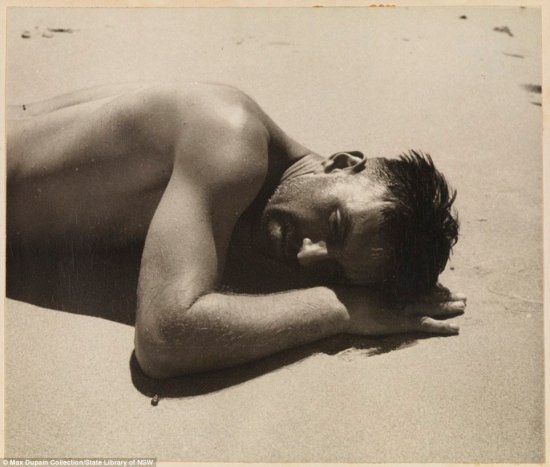

Max and Olive is an exhibition at the Ian Potter Museum at Melbourne Uni that looks at the work of Max Dupain and Olive Cotton, two important Australian photographers. It focuses on the period of their close professional association, and brief marriage, the years of 1934 to 1945. It closes on July 24, so run, don’t walk, to this fabulous show.

The exhibition is a fine-grained analysis of their vast and progressive output, and draws out much about the period and the social context. The two worked in every genre and evidently set a new standard in Sydney for modern photography. The studio, opened by Dupain in 1934 (at the age of 23!) was immediately successful and he worked prominently in fashion, portrait and advertising photography.

In 1937 the studio was commissioned to photograph the Hungarian String Quartet which was visiting Australia on a tour. The two resulting photographs in the exhibition show a clear difference in aesthetic temperament between the two photographers.

Cotton, who was Dupain’s studio assistant, photographed the four musicians as a team, emphasizing the relationship between them as they performed a serenade by Tchaikovsky. ‘”I wanted to get the feeling of a group making music that they loved,” she said.

Dupain’s image is more theatrical, with one player, possibly the leader, heroically lit while the others are in subdued light and moved to the side. Where Cotton’s is an image of equality, Dupain’s is one of hierarchy. In this respect the twin photographs are almost a caricature of the gendered gaze.

A further example of their different style is in two landscapes, again taken in the same year and including similar ingredients. Once more, Dupain’s is a forthright composition with strong emphasis and contrast. He makes his statement boldly and clearly; he once quoted Lewis Mumford’s statement that “the mission of the photograph is to clarify the subject.”

Cotton’s image is more equivocal. She is juggling more elements and they are linked in an almost circular visual path. It is not as clear and decisive as Dupain’s and suffers a little from indecision, but as a scheme it reinforces the impression given by her Hungarian violinists. Cotton’s work is more about relationships, while Dupain is looking for heroes.

Max Dupain, Bawley Point Landscape, 1938

Max Dupain, Bawley Point Landscape, 1938

Olive Cotton, The Patterned Road, 1938

Olive Cotton, The Patterned Road, 1938

The exhibition Max and Olive is a special event, the first to look at the work of these two historic figures together. While Dupain is clearly the superior artist, Cotton comes out very well. And as a display of fine photographs the show is a revelation, there is much to learn just from how they worked with photography, especially the formal qualities of composition, contrast and print colour etc.

The exhibition is a travelling show from the National Gallery of Australia. It’s website has a complete set of the pictures in the show with text so after you’ve seen the exhibition you can review it at leisure on a computer. Just make sure you see it at the Ian Potter Museum first.

Greg Neville, Waiting man, 1971

Greg Neville, Waiting man, 1971