Isabelle Le Minh, Objektiv, after Bernd & Hilla Becher, 2015

Isabelle Le Minh, Objektiv, after Bernd & Hilla Becher, 2015

Isabelle Le Minh is a French artist who works on conceptual projects that engage with the history and meaning of photography. Her 2015 work ‘Objektiv, after Bernd & Hilla Becher’ featured in the recent curated exhibition Déconstruction Photographique at the Paris gallery Topographie de l’Art.

Objektiv is an hommage to the Bechers who refined the mode of photographic typology with their well-known grids of industrial structures. Le Minh substitutes the Bechers’ water towers and blast furnaces with a collection of antique Petzval lenses from the 19th century. Like the Bechers subjects, her lenses, once advanced products of industry, are now historical artefacts, and are studied through their typological variations.

Her pictures resemble the Bechers’ images both in composition and print quality – her individual prints are as beautiful as black & white can be. The overall similarity is striking and, after you smile, you begin to pay close attention.

The title, Objektiv, is a clever choice as it’s loaded with meanings. First, it is the German word for lens, the subject-matter of the series. Further, these photographs are close ups of things, like still lifes – the lenses are objects.

The word also refers to the objectivity with which a lens transmits light. It is in the DNA of photography that the image is captured ‘impartially’ as a phenomenon of physics, not art. Unlike, for example, in a painting where the artist’s interpretation is unavoidable a photographic image is recorded automatically by light. This is the teasing ambiguity at the heart of the medium – photographs are recorded by a machine and always seem to be artefacts of the real, visual world.

So what is the objective of Le Minh’s project? It is so much more than a mere echo of the Bechers’ work. Objektiv is a solipsistic work. It copies the methodology and style of a project from photographic history, the Bechers’ work, and reminds you that a photograph is always about photography and always about the history of photography.

It uses a lens to record lenses, a machine to record machines and so is about the thingness of photography, As her gallery’s statement asks, “Aren’t photography’s technical objects more singular than the images they can produce ?”

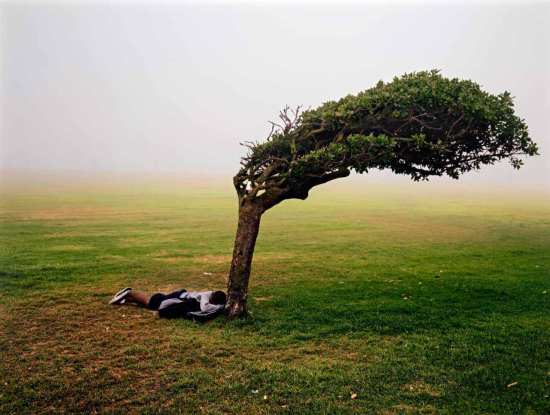

Bill Brandt, Francis Bacon, Primrose Hill, 1963

Bill Brandt, Francis Bacon, Primrose Hill, 1963

A

A